Despite advances in agriculture, around one third (34%) of the population of sub-Saharan Africa is still undernourished – very little different from 20 years ago (37%).

Also, despite the devastating impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the population of Africa is expected to increase from its current level of around 794 million to at least 1.7 billion by 2050, with upper estimates of around 2.3 billion by the year 2050.

At the same time as these trends, the incidence of diseases seems to be increasing – partly as a result of the deregulation and decentralization of public health and national pest management operations. For example, the cessation of fogging for capsids in Cameroonian cocoa plantations seems to have coincided with an increase in blackflies and mosquitoes. The cessation of residual house wall spraying has certainly resulted in an increase in the numbers of mosquitoes.

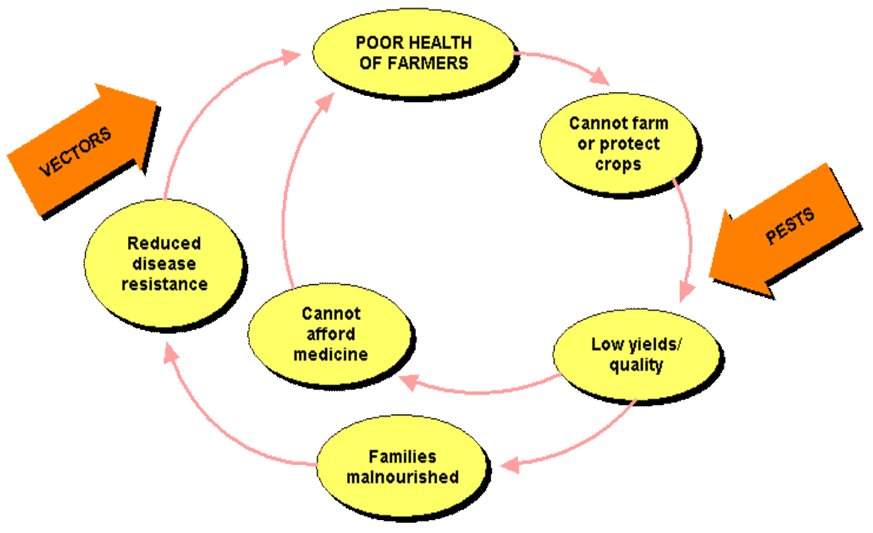

Productivity is seriously affected by the diseases transmitted by these insects, namely onchocerciasis (river blindness) and malaria. River blindness results in a high proportion of some village populations becoming blind, and malaria kills 3,000 people per day across the world.

Even when African families are fit enough to cultivate successfully, their crops suffer frequent damage from pests, diseases and weeds, resulting in production losses estimated at 50% and reduced, less saleable quality. The response, in the absence of information on alternatives, is often the use of pesticides by untrained people, who are wearing little if any protective clothing, applied through poor quality and/or defective spraying equipment. The result is variable crop protection success, contamination of the operator and the environment, and excessive residues in produce which, at the very least could mean loss of market access due to rejection of produce, and at worst, health hazards to consumers.

These vector and pest problems are interlinked in that they require safer and more effective control strategies that involve pesticides, but involve them in a more integrated way with cultural, biological and physical measures taken as much from indigenous knowledge as from modern research innovations.

The nuisance potential of black fly is also enormous with reports of people being bitten hundreds of times per day, making productive work impossible. People have moved away from rural areas to cities and do not wish to return because of the impact of these vectors and nuisance insects on their lives. This urban drift is a major trend – 30 years ago, less than a quarter of Africa’s population lived in cities, but by 2025 it is projected that over half will do so.

The ever-expanding population will require increasing quantities of food, produced by a diminishing rural proportion of the population, whose productivity is severely constrained by ever-increasing disease incidence.

Recent Comments